Did Clay Shaw Get the Help He Deserved?, Part Nine

- Fred Litwin

- Nov 2, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 3, 2025

The Bonderman Memo

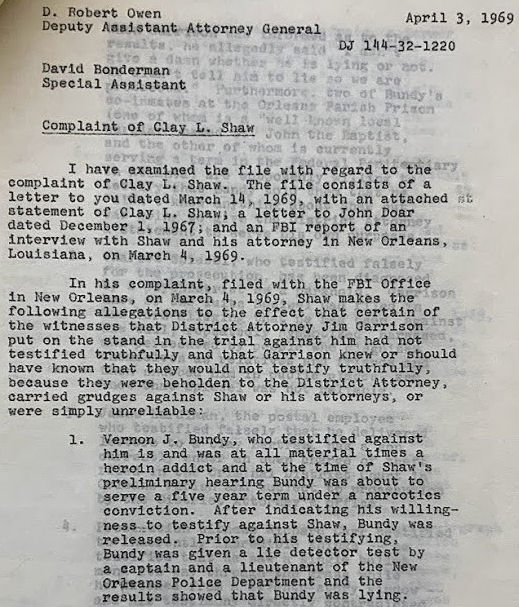

David Bonderman, a special assistant in the DOJ, was given the task of reviewing the materials submitted by Shaw's attorneys.

Here is his memo from April 3, 1969:

Bonderman writes that "prosecutorial discretion covers at least the right to make bad, erroneous, and even silly decisions."

The civil rights laws do not envisage examinations into the quality of testimony given, and therefore, as to the allegations which deal with the unbelievability of certain testimony it would appear that, taking a view of the allegations most favorable to Shaw on the evidence, no possible claim of violation of any of the laws enforced by this Division would be made out.

But Bonderman realizes that two the allegations made by Wegmann in his December 1, 1967, letter to John Doar, are "somewhat different."

As to Alvin Beauboeuf and Fred Leemans, Wegmann alleged that members of Garrison's staff attempted to bribe them with payments of substantial sums of money in order to get them to testify falsely against Shaw, although neither of them did. It seems clear that prosecutorial discretion does not extend to bribing witnesses to give false testimony and I can see no reason why 18 U.S.C. 241 and 242 do not cover this sort of activity for this is essentially an allegation of conspiracy, under color of law, to deprive someone of his rights to a fair trial by suborning testimony. Thus it appears that if the allegations are true, there is the sort of situation which would conceivably fit in with our priorities for enforcement.

Bonderman not only contradicts the DOJ's prior position that there was no "statutory basis" to act on Wegmann's complaint, he also presents the specific code and sections.

Patricia Lambert wondered why Pollak didn't see in 1967 what Bonderman saw in 1969. And Bonderman provides the answer:

I understand that a decision was made not to investigate on the ground that involvement with the Garrison investigation would be of marginal value for our law enforcement efforts at best, and that the totality of the allegations made by Wegmann at that time were not weighty.

Here is how Patricia Lambert translates his words:

Quite simply it means the government had no intention of intervening in the New Orleans thing regardless of what laws Garrison might be breaking. The action of Stephen Pollak rejecting the complaint in early 1968 is entirely consistent with the attitude permeating the tape-recorded conversations between President Johnson and Ramsey Clark that took place the previous year. Both men exhibited an exaggerated concern, fear even, that the government might do something that would trigger a response from Jim Garrison. When Pollack rejects the complaint, Johnson is still in the White House and Ramsey Clark is still his Attorney General.

Then, too, there are those once-secret CIA and Department of Justice files concerning the request of Shaw's attorneys to meet with the CIA. Those records, and others (including some from the FBI) reveal two previously unknown facts. First, the Department of Justice was in charge of the government's decision-making process regarding the Garrison-Shaw matter -- everyone, including the CIA, received their marching orders from Ramsey Clark's department. And, second, someone there decided to avoid entanglement at virtually any cost --even, apparently, if that cost was twenty years of an innocent man's life. What the records don't reveal, that remains unknown today, is who made that decision and why.

Of course Bonderman does leave open the possibility of investigating "at a later date." But he decides not to investigate now because of "the general problems in getting involved in the Garrison probe."

Lambert continues:

Bonderman probably did all he could do for Wegmann and for Shaw, and unwittingly he did something else. By speaking truth to power (even in his limited way), Bonderman embedded that truth in the documentary record of this case. His voice is one of those from the past informing us today. His memorandum shows Department of Justice officials so determined to keep their distance from Garrison that they abnegated their responsibility, statutory and moral, to Clay Shaw. They simply threw him to the wolves. That he was not devoured is no thanks to them. He was saved, in the final round, not by his innocence alone, but by Edward Wegmann's federal strategy and unremitting outrage that the rights to which all Americans are guaranteed were so blatantly violated in Shaw's case.

In one of those 1967 telephone conversations with President Johnson, Ramsey Clark expressed dismay that Garrison had not "immediately" reported whatever information he had on the assassination to the Secret Service and the FBI "as being a matter of national concern [and] responsibility. But the government had a responsibility too. The President and the attorney general were personally aware of the vacuum underlying Garrison's investigation. Didn't that knowledge bestow on them a duty to use their extraordinary authority on behalf of a man they knew to be an innocent victim of a mad charade?

Had the decision makers at Justice investigated the bribery charges, Garrison surely would have cried Government cover-up, thereby fulfilling the prediction voiced by Lyndon Johnson to Ramsey Clark. At that point, however, the main-line media no longer trusted Garrison, they were on to him, and the facts would have supported the government's action. That window of time, from December 1967 through May 1968, was the perfect moment for the government to stand up to Garrison, a moment that would not come again. Instead of seizing the moment, the decision makers behaved as though Wegmann was asking them to dive head first into a landfill of nuclear waste. They were just as determined to keep the government out of the case as Wegmann was to draw them into it.

Their refusal to do the right thing in this instance is the first step to the larger government failure that follows, and its consequences. Garrison's glorification and Shaw's conviction by cinema are not the worst of those consequences. The worst is the widespread conspiratorial mindset of today's popular culture. That mindset wasn't born in a 1991 Hollywood movie. It was born in New Orleans in 1969 at Clay's trial when Garrison staged the first public showing of the Zapruder film and claimed to know what it meant. In that theatrical courtroom moment, Garrison defined the meaning of President Kennedy's assassination in the popular imagination. That conspiratorial mindset, which has been poisoning and dividing this country ever since, the government could have throttled in the womb.

Here is the letter that was sent to Edward Wegmann:

Lambert also has a few other choice paragraphs about Garrison and conspiracy theory:

On the plus side, one quite important discovery surfaced during the inquiry [HSCA]. (Actually, it had surfaced earlier but the Rockefeller Commission did not pursue the issue as fully as this committee did.) The HSCA obtained scientific analyses of the president's backward movement, as shown on the Zapruder film which, in effect, debunked Garrison's interpretation of it which he proclaimed at Clay's trial -- that it showed a shot from the front and proved a conspiracy occurred. The expert opinions assembled by both the Rockefeller Commission and the HSCA dispute that interpretation, and their opinions have been reinforced and supplemented by others over the years. Garrison got it wrong. The Rockefeller Commission knew that and so did the House Committee. Yet neither made any effort to publicize what the experts had said about that issue, they omitted the information from their public reports, and to this day it is basically unknown to the proverbial man in the street. This was another golden opportunity missed.

Instead of strengthening America's confidence in its government, as Clay envisioned, these investigations would fuel the country's appetite for conspiracy, which today borders on a bulimic-like pathology. Any theory, no matter how outrageous, has a following as long as it says the government did it, whatever it might be. Many factors contributed to the decline in public trust. But the unchecked paranoia now rampant in the land began with Garrison -- he was the initial carrier, the infecting agent, both in what he said and what he did.

His public attack on the CIA -- all those relentlessly escalating lies -- helped set the stage for what followed. His illegal dissemination of the Zapruder film (some thirty years before commercial copies became available to the public) was a stealth-like demarcation, not widely known even now almost forty years after the fact. A chess player and a strategist, Garrison knew what he was doing. By passing out bootleg copies of the film to certain individuals who shared his views, copies he knew would be reproduced repeatedly over time, he was secretly feeding, creating and enlarging an underground conspiracy constituency. He was using the most emotionally charged evidence in the case (obtained solely through the power of his office) to promulgate his false version of the assassination and guarantee that his influence would be ongoing. At least in the courtroom he did it legally and in the open: He spelled out his misinformation to media representatives from around the world. Today that misinformation is what most people believe. The jury acquitted Clay, but ignorance and the Zapruder film in time trumped their verdict. And that twenty-six second slice of history remains today the most evocative, misused and misunderstood evidence in this case.

I have one thing to add. Lambert was right that the investigative bodies never really countered the JFK head snap narrative. That is why we are indeed fortunate that Nick Nalli has written some very important scientific papers on the JFK assassination:

It's a pity that Patricia Lambert did not finish this book. Her insights and her research talents would have added substantially to the canon.

I was very fortunate to have two opportunities to examine her papers at the Sixth Floor Museum. She was a terrific researcher -- she interviewed everybody possible. James Phelan acted as a sounding board. They exchanged numerous letters about her research and his personal knowledge of Jim Garrison. Paul Hoch, an astute JFK researcher, also provided a lot of feedback to Pat. They both contributed to Pat's enduring legacy of having written one of the best books on Jim Garrison.

Patricia Lambert died on May 10, 2016. R. I. P.

NEXT: Conclusion.

The Clay Shaw Series

The setting in New Orleans

The DOJ is told not to get involved. The FBI follows suit.

Ed Wegmann goes to Washington.

The CIA gets involved.

Wegmann goes back to Washington with Irvin Dymond.

Wegmann files a civil rights complaint with the Department of Justice.

Wegmann files a forty-five-page complaint in the U.S. District Court in New Orleans.

Clay Shaw's Acquittal; New Charges; and Wegmann Goes Back to the Department of Justice.

The new Department of Justice, under President Nixon, considers Shaw's new civil rights complaint.

Conclusion -- and a case study in how a conspiracy theorist gets it wrong on Clay Shaw.